|

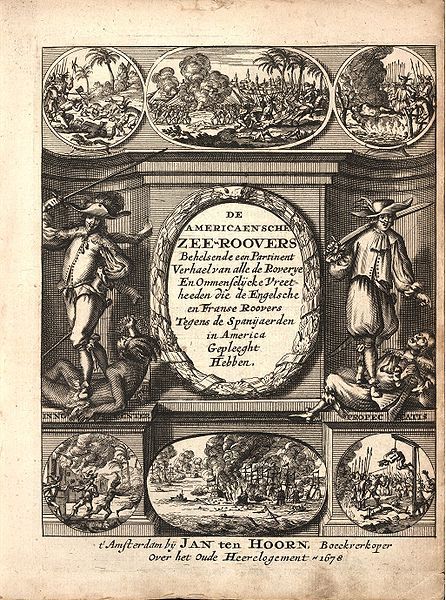

| The 1678 original |

Most pirate fans know that the go-to book for the buccaneer era is Alexander Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America, originally published in Dutch as De Americaensche Zee-Roovers in 1678. Typical of historical accounts this old, the history of the book and its author are complicated and full of questions. Is it Exquemelin, Esquemeling, Exquemeling, or Oexmelin? That Exquemelin was a real person can safely be assumed, and his accounts can be verified by other sources, but who he was is total conjecture. It seems likely, based on the available evidence, that he was from Harfleur and that he was a Huguenot, his religion driving him from France and to indenture himself to the French West India Company and sail to the Caribbean. Regardless of holes in his biography, it’s clear that Exquemelin is the real deal: Exquemelin landed in Tortuga in 1666, and three years later, once free, he joined the buccaneers. He sailed with, most notably, none other than the most famous buccaneer of all, Henry Morgan, probably as barber surgeon. Later, in Amsterdam, at about the same time he was writing the book, he qualified professionally as a surgeon; does that make Exquemelin the pirate Maturin?

|

| The modern Dover edition |

I have used Exquemelin as a reference book but until recently had never just sat down and read it all the way through. I thus want to consider The Buccaneers of America as a whole, not as a collection of the tales of Morgan, Rock Brasiliano, etc. Through a combination of detailed historical account, amateur ethnology, and natural history, Exquemelin portrays a wild place populated by brutal men. The author's own style is direct, but to me it is unclear whether it is detached or, in fact, unsympathetic. Exquemelin and his buccaneers are not romantic, tho' they are colorful. Most importantly, these earliest pirates of the Caribbean are bloody players on a colonial frontier in which men regularly killed each other for religion, country, gold, and simply to survive.

It’s worth leading with a quote not from Exquemelin himself but from Jack Beeching, who wrote the introduction to the 1969 Penguin Books translation, now in paperback form from Dover. Writes Beeching: “Most of the men who ravaged the Spanish Main spent their plunder quickly, in furious debauch, and at once put to sea for more, like frenzied victims of some contemporary infection, a gold-fetishism, a thing-fever.” Putting aside the marvelous language—and the idea that piracy is disease, perhaps akin to the gold fever that once afflicted Old West prospectors—the central idea is that the buccaneers lived fast, hard, and often short lives. Exquemelin describes them almost ubiquitously as cruel, but then his portrait of the Caribbean in the 17th century makes everyone out as cruel. For instance, Exquemelin writes, “These men are cruel and merciless to their bondsmen: there is more comfort in three years on a galley than one in the service of a boucanier.” Two pages later, Exquemelin describes how the Spanish on Hispaniola are always patrolling for the boucaniers but hope they don’t actually find them. The Spaniards “have not the courage to meet them in the open field, but try to spy out their whereabouts and do away with them in their sleep.”

|

| The boucanier, from an early edition of Exquemelin |

|

| Another classic illustration from Exquemelin |

Roughly half of the book is dedicated to Henry Morgan, but then not only did Exquemelin sail with the infamous Captain but also there are a lot of now legendary escapades to document: Porto Bello, Maracaibo, Panama. After his book was published, Exquemelin was, in fact, sued for slander and libel by his former commander. The rise of Morgan marked another critical turning point in the definition of buccaneer. One, Morgan was an Englishman, or, rather, a Welshman. This did not always sit well with the true buccaneers. After the capture of Puerto del Principe, "trouble broke out between the French and English because an Englishman had shot a Frenchman dead on account of a marrow-bone;" the disagreement escalated until the French left Morgan's group entirely. Similarly, at the beginning of the Maracaibo expedition, the French were afraid of reprisal for recently taking an English ship for its food. An English ship then mysteriously exploded, and the English responded by accusing the French of having a secret Spanish commission and commandeering the French ship. Two, Morgan was, at least arguably, a privateer. He came from a military family and as a soldier participated in the British capture of Jamaica. Early in his career, Morgan gained a letter of marque from Governor Thomas Modyford of Jamaica, in spite of the fact that the King had just issued a royal edict forbidding acts of violence against the Spanish. It worked out rather well for everyone; Modyford had a private army, the pirates had a 'legal' reason to pillage and plunder, and all of it fed into the economy of the Caribbean's new boom town, Port Royal. Three, as a consequence of Morgan's new combination of nationalism and greed, the buccaneers were another, large step removed from their origins as outcast hunters. If anything, they were now hired mercenaries. This allowed Morgan an incredible scale of operations: He began the Panama expedition with 2,000 men and 36 ships. It all eventually escalated to the point that it could no longer sustain itself.

The cruelty of the buccaneers remained, indeed intensified by Protestant English hatred for the Catholic Spanish but still driven by the thing-fever. I will quote Exquemelin from his account of the capture of Maracaibo. Here Morgan and his men have just captured an old Portuguese man who insisted that he did not have any hidden money.

The rovers did not believe him, but strappado'd him so violently that his arms were pulled right out of joint. He still would not confess, so they tied long cords to his thumbs and his big toes and spreadeagled him to four stakes. Then four of them came and beat on the cords with their sticks, making his body jerk and shudder and stretching his sinews. Still not satisfied, they put a stone weighing at least two hundredweight on his loins and lit a fire of palm leaves under him, burning his face and setting his hair alight -- yet despite all these torments he would not confess to having money.

|

| Henry Morgan and his crew in Portobello, as depicted by Howard Pyle in 1888 |

Exquemelin describes much the same for Panama City, yet Morgan's biggest endeavor was also an extraordinary failure. Most of the valuables had been sent out of the city by the time Morgan captured it. Morgan sent a barque after the fleeing treasure ships, but the galleon loaded with the King's silver and the jewels of the foremost merchants slipped away in spite of being minimally armed and under reduced sail. Then the city was set ablaze. According to Exquemelin, Morgan ordered this himself but "started a rumor that the Spaniards themselves had done this." This may have been the author's own bitterness as a French--and Catholic--buccaneer seeing the promise of the enterprise literally up in flames. Modern historians (eg, David Cordingly) state that the Spanish captain of artillery remained in the city and followed orders to torch the city's scattered powder magazines. What is clear is that by the end of the blaze very little of Panama City was left. There was also, even after over two weeks of digging through the ruins and interrogating prisoners, not nearly enough booty to satisfy the huge army. Morgan's men accused him of keeping more than his share, and Morgan sailed without the rest of his fleet to outrun the rumors of duplicity. He returned to Port Royal to find that his raid was illegal. The Treaty of Madrid in July 1670 had officially ended hostilities in the Caribbean between Spain and England, but the news did not reach Jamaica for nearly a year, by which time Morgan's mission was well underway. Modyford and Morgan were both arrested and returned to England, but this was really only for diplomatic show. Although Modyford spent two years in the Tower of London, he eventually returned to Jamaica as Chief Justice. In the same amount of time, Morgan was applauded, knighted, and appointed Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. Although rich and respected, the soldier was out of his element and started living like a true old pirate, drinking and carousing. He died of alcoholism and dropsy in 1688 at the age of 53 and was buried with official honors and a firing of the guns by the British warships in Port Royal harbor.

|

| A map of Central America from the mid 17th century |

The disappointing raid on Panama was the beginning of the end of the Buccaneer Era. The French who had been abandoned my Morgan returned to their old ways on Tortuga; others joined the logwood cutters on the Bay of Campeche. Among those left to make their own way after Panama was Exquemelin. Interestingly, at this point in Exquemelin's narrative he returns to what may be his true interest: naturalist and ethnographic description. He spends two early chapters describing the flora and fauna of Hispaniola, from the varieties of palm tree on the island to caimans and birds. Exquemelin's personal account of voyaging up the coast of Costa Rica after the debacle of Panama includes notes on the cultures of the native populations from the bay of Boca del Toro to Cabo Gracias de Dios ('Cape Thank God', part of what is now known as the Mosquito Coast) and descriptions of monkeys and manatees. One wonders if this is what Exquemelin considers to be his true calling, or whether he is playing to the armchair travelers buying his book...not that these are mutually exclusive.

The last chapter, however, shows with a final, vicious note that cruelty is still central to Exquemelin's message. Here he describes how Bertrand d'Ogeron, Governor of Tortuga, attempted to lead an expedition against the Dutch in Curaçao only to find himself and his men shipwrecked on Puerto Rico and in the vengeful hands of the Spanish. The Governor and his barber-surgeon were the only ones to escape the brutality of the Spanish, and the two gathered buccaneers from Hispaniola and Tortuga to attempt to save the lost crew. The rescue attempt was a failure, the Spanish being alerted and too numerous to overcome. "M. d'Ogeron managed to save his life, although he was half dead with grief. His attempt had failed, and the men left behind in the hands of these barbarous people would have to pay for it....The Spanish stayed on shore until d'Ogeron's ships were out of sight, then killed off the wounded, cutting off nose and ears of the corpses to take back and show the other prisoners, as a sign of the victory they had won." Those lucky enough to be enslaved instead of killed were sent to San Juan and thence to Spain. Some managed to get to France and sailed right back to Tortuga, and "many went out marauding again."

|

| "The Buccaneer Was A Picturesque Fellow" by Howard Pyle, 1905 |

Like any work that is 300 years old and has gone through numerous translations, it is difficult to read the true perspective behind The Buccaneers of America. It is a first-hand account, but it almost seems to hold its subject matter in contempt. Did Exquemelin regret his past? Was he a scientist, or was he just trying to sell books? Whatever motivations may have been behind its writing, Exquemelin's book is without a doubt the greatest single source on Caribbean piracy of the era. But if you read it, don't expect any dashing Errol Flynn. Expect blood, not Captain Blood.

I think this is one of your best posts ever, Lou. Thank you so much for it. I hope you don't mind me linking to it over at Triple P (especially for International Talk Like a Pirate Day :)

ReplyDeleteI hope you're doing quite a bit better and, just a little meta here, my Mom - who is a retired RN - used to work at Overlake Memorial. Super. Small. World.