That a non-fiction book can be a page turner might be weird to some, but Jay Bahadur's

The Pirates of Somalia was completely riveting. Bahadur is a journalist, but he's also in a way an anthropologist: He clearly knows that facts gathered from real fieldwork and with real cultural sensitivity are far better than second-hand information and armchair analysis. Rather than extol his writing, however, I'm going to put here some of the facts about Somali pirates that not only struck me but also would be well to remember in any future discussion.

|

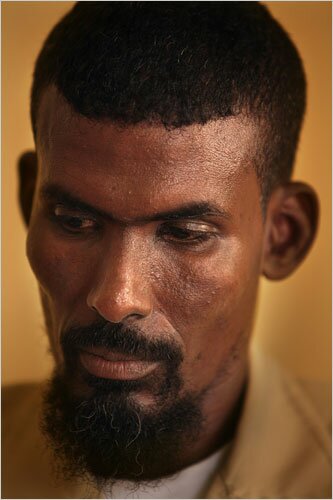

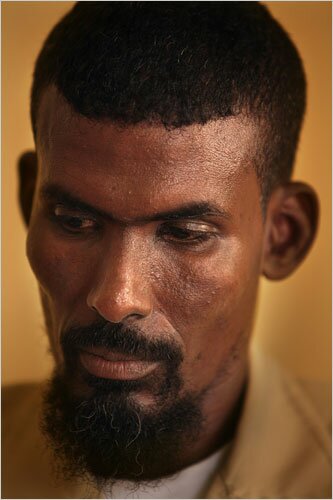

| The pirate Boyah |

1.

Somali pirates are not all the same. The historical timeline of piracy in Somalia shows that pirates have different origins, motivations, and methods. Bahadur describes three "waves" of piracy. The first wave, beginning roughly with the collapse of the central Somali government in 1991, consisted largely of "marine muggings." This was the mythical era of the fisherman-pirate, struggling against outsiders first by taking on foreign trawlers and then by attacking any passing, worthwhile target.

Eyl was the pirate haven of the day, and one of the chief operators was Abdullahi Abshir, better known as "

Boyah," one of Bahadur's main subjects. The second wave began in 2003 with the rise of Mohamed Abdi Hassan, alias "Afewyne" ("Big Mouth"). Afweyne was--and is--a businessman, and his "Somali Marines" out of the ports of

Harardheere and

Hobyo are organized in a military fashion. The targets got larger: A joint operation between Eyl and Harardheere, crossing not only geographical lines but also clan lines, captured the now-famous

MV Faina with its load of tanks. Yet, in spite of bigger targets and bigger ransoms, these pirates called themselves "Coast Guards" to at least

look they were protecting Somalia from evil foreigners. As recently as

February 2011, Afweyne has been described online as a "Robin Hood" for Somalia. The third wave began, perhaps, in 2008, when the security sector in Puntland collapsed, leaving trained men unemployed and available to go on the account. Bahadur calls these most recent pirates "opportunists" on the coattails of men like Boyah, Afewyne, and a third kingpin, Garaad Mohammed, who has taken credit for the

Maersk Alabama. Garaad has recently

gained attention when the ransom intended for the MV

Yuan Xiang, captured by men under his command, was seized in Mogadishu, resulting in the

arrest of three Britons. The lesson here is simply that the Somali pirates should not be viewed as a unified force: Time, place, and culture make each group unique. The one constant is the "fisherman" story, which now must be seen as a public relations strategy not a universal fact.