That a non-fiction book can be a page turner might be weird to some, but Jay Bahadur's The Pirates of Somalia was completely riveting. Bahadur is a journalist, but he's also in a way an anthropologist: He clearly knows that facts gathered from real fieldwork and with real cultural sensitivity are far better than second-hand information and armchair analysis. Rather than extol his writing, however, I'm going to put here some of the facts about Somali pirates that not only struck me but also would be well to remember in any future discussion.

|

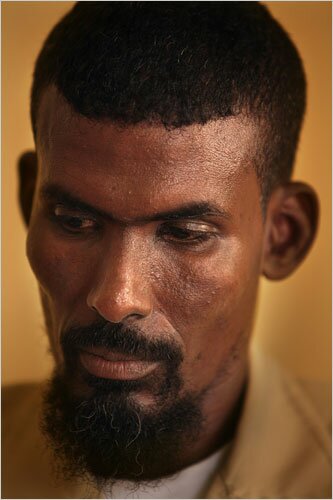

| The pirate Boyah |

|

| Garowe, the capitol of Puntland |

2. It's all about Puntland. Forget about Mogadishu and the Islamic madness of the south. A self-governing state that, however, still considers itself part of Somalia (unlike its neighbor and rival Somaliland), Puntland is not only the birthplace of modern Somali piracy but also the best bet for fighting it. Its location on the Gulf of Aden puts Puntland next to the major shipping lanes. It is away from the war and thus more stable than the south, but it is ungoverned enough to give the pirates room to operate. A drought from 2002 to 2004, followed by a tsunami, devastated the area's subsistence and drove men to desperate measures. Hyperinflation ruined the economy. The government has all but broken down; as mentioned before, unemployed soldiers go pirate (which is, of course, as it was centuries before in the Caribbean). Yet this feeble state is, according to Bahadur, "all we've got." If the solution to Somali piracy is on the ground and not on the wide sea, then strengthening Puntland is critical. Bahadur argues that financing a well-trained police force would both create jobs and catch the pirates before they reach the ocean. An expansion of the prison system would create a place to put those caught. Coordinating intelligence between Puntland and the Naval fleets would work to the benefit of both. In short, simply referring to piracy off the Horn of Africa as "Somali" ignores the specifics of its rise and its possible decline.

3. The myths that power international media attention on the Somali pirates simply aren't true. A whole chapter of the book, "Pirate Lore" (which begins with a short bit on the pirates of old), is dedicated to mythbusting. One, Somali waters are not "teeming" with pirates. Bahadur cites a 2008 statistic from the International Maritime Bureau: The average ship has less than a 1 in 550 chance of being taken...although, as the pirates continue to get more daring, I suspect the odds may be a bit greater. Two, the pirates are by no means even on good terms with Islamic extremists, much less beholden to them. Although the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) has pushed north as far as Harardheere, most pirates consider working with Islamists simply bad business; ties to Al-Shabaab would call quick and lethal foreign attention to pirate activity. In fact, pirates in Hobyo have actively resisted the ICU. Three, there is no international cartel that backs Somali piracy. Certainly there is an international diaspora--there are Somalis here in Seattle--but contacts overseas do not constitute a crime network. Pirate bands form for missions and break up as soon as they're done, Dons like Afweyne and Garaad aside. Four, the pirates do not have a complex intelligence network. There's no need for one: There's enough traffic in the shipping lanes that it works to simply get there and wait for weak prey. These busted myths are not meant to downplay the seriousness of Somali piracy. Nevertheless, Somali pirates are not taking over the ocean, are not terrorists, are not the Mafia, and are not post-modern criminals.

|

| Inspecting khat at a vendor in Bosasso, Somalia |

4. The common Somali pirate does not become an overnight millionaire after a successful mission. Bahadur proves this by doing a detailed "audit" of divided ransom vs. expenses for a hijacking that occurred while he was in Somalia, the taking of the MV Victoria by a crew under the mysterious, purportedly psychic "Computer." The ransom itself was $1.8 million. The expenses for the gang during their 72 days aboard Bahadur estimates at $230,644. Although transportation and fuel, guns and ammo, and food and beverage (including two goats!) are all significant costs, the biggest single expense is the Somali pirate's answer to rum: khat, a plant that is chewed for its amphetamine-like effects and that Bahadur describes as teetering between "a tolerable vice" and "a national addiction." Bahadur states that nearly $110,000 may have been spent on khat for the crew holding the Victoria. Computer, as is normal for a Somali pirate gang leader, is responsible for these expenses, but he also takes a full 50% of the prize money. Attackers get larger shares, and the first aboard gets a bonus. "Holders"--those who essentially babysit the ship as they wait for the ransom to get paid--get perhaps $12,000 for their time, and this money is quickly gone to family, friends, and creditors (usually an advance for more khat). The only one who gets any real fortune is Computer as organizer, investor, and commander. The lowly seaman, if you will, gets little more than a spree on shore and a tiny degree of notoriety and peer respect.

|

| A mosque in Puntland |

6. The role of Yemen may not at all be what I thought. Bahadur describes Yemen not as another potential pirate haven but as a Somali target. With the Yemeni side of the Gulf less patrolled than the Somali side, Yemeni fishing vessels are easy pickings. Their vessels are sometimes turned into motherships. The Somalis, according to one source, may even pretend to be Yemeni fishermen. In spite of what would thus seem to be antagonism, Yemenis and Somalis regularly cooperate on one thing: smuggling, including weapons, equipment, and people. Since the Somali pirates are already going to Yemen for guns, it has become profitable for them to also ferry refugees. This side enterprise also provides a sort of cover from the government and the Naval brigades. Bahadur does not at all discuss the unrest and instability of Yemen itself, but that's not the purpose of the book. With these new perspectives on the "Yemen Connection," however, it is clearer to me that even the proposition that Yemen could be the 'next Somalia' is, at least at this point, very speculative.

|

| French frigate Nivose of EU NAVFOR, and typical small pirate skiffs |

7. It's not about the Navy. Consider the the odds. The area of pirate attacks ranges from the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean, and from Oman to Madagascar. There are perhaps 2,000 pirates at any point in time, but their groups are usually only six to twelve people. There is a window of between fifteen and forty minutes between when a ship spots pirates and when the pirates board for a ship to respond. This is my favorite line of the book: "For the crews of the warships in the combined international naval effort...hunting pirates must seem like playing a losing game of Whac-a-Mole." In 2009, of pirate attacks successfully averted, fewer than one in six were the result of direct intervention; smart crews that detect the pirates early, speed up, and evade the attackers make more of a difference. And the Naval effort costs over a billion a year!

8. The future is bleak. In an appendix, Bahadur assesses the situation just shy of the book's publication in 2011. Ransoms are getting larger. The pirates are getting more organized. Encounters are getting more brutal. "With the cost of attacks increasingly likely to be measured in blood in lieu of dollars, bringing a swift end to the scourge of piracy has never been more imperative." (I love the word "scourge.") As followers of this blog know, instead of real efforts to strengthen Puntland itself, we have the "Jeffersonian" response. To say the least, I have a much fuller and more detailed picture after reading The Pirates of Somalia. But what are the Somali pirates? If they're not heroes, are they villains? If they are both legal criminals and religious untouchables, are they on any body's side but their own? Are they, as Bahadur states at one point, to be compared to inner-city drug dealers, youth seeking status by any means necessary in a place of overwhelming desperation? This begs another comparison. Would drug dealers or pirates stop doing what they're doing if they were given brighter alternatives? Bahadur argues this early in the book: To stop piracy, not only must the sea be made less attractive, but also the land must be made more attractive. Don't hold your breath. But do keep watching...

No comments:

Post a Comment