|

| Warton Marsh on the Ribble Estuary, from the blog ribbletoamazon.com |

The port of Liverpool was only about thirty miles away. The most obvious route would have been directly south, but this led through Wigan and thus in the direction from which General Wills had brought his troops. Luckily for Logan (and, for me, the writer), the geography of the area gave him a way to travel that few if any people would notice. West of Preston, the River Ribble broadens into a massive estuary. Even today, thanks to preservation as a National Nature Reserve, over a quarter of a million waders and waterfowl winter in the area. The region was sparsely populated, limited to small, scattered fishing and farming villages such as Banks and Churchtown in the ancient parish of North Meols that had been settled by the Norse before the Norman conquest. By keeping to the marshes, Logan would have been seen by no more than thousands of birds such as wigeons, geese, and plovers. The going was slow, muddy, and treacherous. Eventually, south of what is today the seaside resort of Southport, the wetlands would have given way to miles of beach and sand dunes. The flat, broad West Lancashire coastal plain saw Logan all the way to the outskirts of Liverpool.

|

| A 1917 map of the Ribble Estuary |

For this post and the next, my major source is one of the best books on maritime history I own, Marcus Rediker's Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates, and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 1700-1750. In a future post, I will come back and look at this book at length academically. In brief, Rediker analyzes the "seaman's dilemma" described metaphorically in the title: "One one side stood his captain, who was backed by the merchant and the royal official, and who held near-dictatorial powers that served a capitalist system rapidly covering the globe; on the other side stood the relentlessly dangerous natural world." Jack Tar could do little to combat the mighty ocean, of course, but he could resist oppression from above, especially through collective effort, and Rediker posits that Jack Tar was the prototypical proletarian before the true Industrial era had begun. Aside from making good scholarly arguments, Rediker also in a single volume gives a thorough picture of the seaman's world--places, culture, work, the sailor himself--at the time of what, for my purposes, I would describe as the Golden Era of Piracy...in other words, Logan's reality.

|

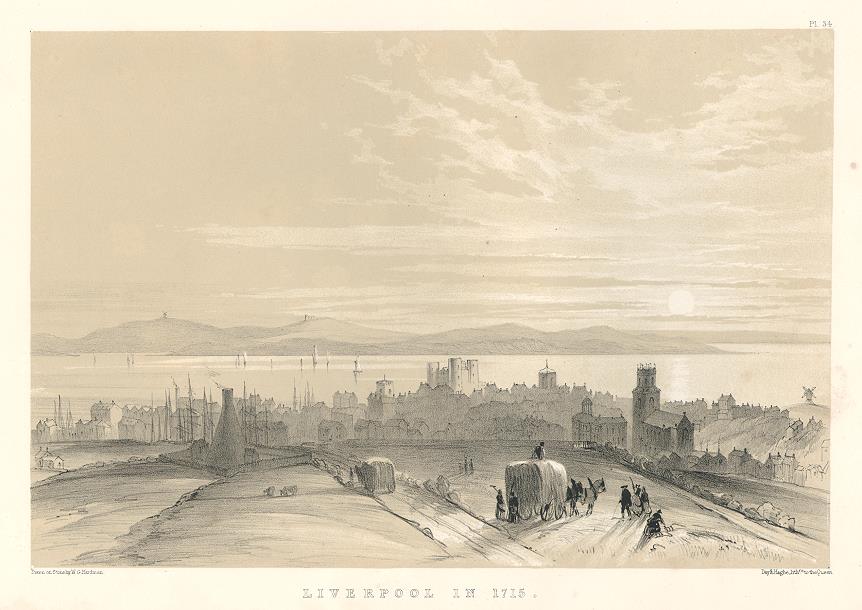

| Liverpool in 1715 |

Liverpool in 1715 was a city very rapidly on the rise. In 1680, its population was only 4,000; by 1740, it was 30,000. This boom was due to growing and profitable trade with the American colonies. As the 18th century unfolded, Liverpool became a key corner in what we would now call the Triangle Trade. From Liverpool came manufactured goods such as linens, glass, and metalwares. The city became increasingly notorious as a starting point for ships bound to Africa for the slave trade, although in 1715 this would have been a relatively young business. According to Wikipedia's entry on Liverpool history, in 1699 the first slave ship in Liverpool's recorded history, the Liverpool Merchant, left the dock, eventually delivering 220 Africans to Barbados and returning home almost a full year after its departure. Coming into Liverpool were the goods of the New World, most importantly West Indies sugar (and rum) and Virginia tobacco.

With more and more people, ships, and money coming into Liverpool, construction rose to meet the demands. The merchants--slave traders and otherwise--had brick and stone structures built on wide streets. In the 17th century, the port itself was the "pool" at the mouth of the River Mersey, which could be up to two miles wide at high tide. Tidal variance and Liverpool's flat, muddy shoreline, however, were no longer amenable to the amount of ships coming in and out. In 1715, not long before Logan's arrival, the wet dock of Liverpool, the first of its kind in the world, was completed. The history of the dock is detailed at "Embryo of a Port 1715," by Robert Storrie, available at Mike Royden's Local History Pages. The mouth of the Pool was backfilled, and in its place was built a brickwalled basin with a massive gate, keeping the water level constant in spite of the tide and able to hold a hundred ships at its quays. What was for a long time called the "Old Dock" was buried in 1811, but in 2001 part of one of the old walls was discovered during development and became an archaeological site. Someday I'll have to go there, as the underground site is now available for free tours. Information on tours of the ruins of Liverpool's Old Dock, including a downloadable brochure, can be found here at the web site for the Merseyside Maritime Museum.

|

| Illustration of 18th century dock construction in Liverpool, by Robert Storrie |

The opulence of the upper class, all paved streets and handsome houses, would not have been the Liverpool Logan saw. According to Rediker, "most of the men who loaded the goods lived in cramped basement dwellings amid workshops and warehouses along the Mersey, on the southern edge of the city." Tim Lambert, in his article "A Brief History of Liverpool," writes that this subterranean housing was, literally, the bottom: "The poorest people lived in cellars under buildings. Often they slept on piles of straw because they could not afford beds." Here, too, would have been the businesses that always served the seaman. Rediker describes the portside world of Jack Tar well for Wapping in London, but Liverpool could not have been much different:

Families and individual boarders, longtimers and transients filled the modest dwellings that crowded the serpentine streets, narrow lanes and back alleys and clustered around the sometimes rowdy music houses the small shops, markets, workshops, and alehouses. Jack and his friends were especially especially fond of alehouse cheer. Whether in search of spirits, food, rest, a short pipe full of tobacco, or game of cards, dice, or ten-bones, or just the latest information on shipping, satisfaction could in these establishments 'run by the poor for the poor.'

Into this scene came Logan, dirty, penniless, and on the run, anxious to be there but just as anxious to get out. In the next chapter, Logan looks for the ship that will, hopefully, transport him to freedom...

|

| "Wapping on Thames" by James McNeill Whistler |

No comments:

Post a Comment